Genuine, Original Romance

Lately I’ve heard about a couple of would-be artists, one even an acclaimed artist whose works command huge prices, flagrantly appropriating, copying, and altering another’s copyrighted work. This didn’t just happen once, and by mistake. It’s a lifelong habit of taking from others. (No links, because these are bad people who have gotten rich by stealing, and I don’t aim to give them more publicity.) This situation, which occurs over and over in many artistic fields, got me to thinking about what constitutes genuinely original, authentic art. Many artists put together collages or pastiches; many popular songs sample older songs. Genre fiction, and romances, are assumed to borrow from each other because of the cliché idea that “they’re all the same.” And they do borrow from each other, or rather, influence each other.

Genre has fashions, fashions in plots and fashions in characters. We’re so used to the particular fashions of our times, whatever they are, that we take questions of plot and character for granted. The stalwart hero, the strong-willed heroine; each has specific character traits that we see over and over in romances. They behave in predictable ways, and their moral compass is already known the moment they enter the story. But someone had to make up these archetypes and their standard stories; they didn’t exist in a vacuum. Who was first? Who “owns” the modern romance hero? Or heroine?

I know who used to own the sex in romances. Barbara Cartland and Kathleen Woodiwiss. Decades ago, they opened the bedroom door, each in a different way. Cartland’s heroines dared to talk about liking marital sex, which was an enormous breakthrough. Woodiwiss was even more daring, using themes involving rape, and semiconsensual sex with a hero her heroine wasn’t yet officially in love with, another enormous breakthrough. In an era in which a “good” girl couldn’t admit to having desire, or single girl to having had sex, each of these authors came up with a groundbreaking way of getting at the truth. The attributes of a romance heroine shifted dramatically. Romances haven’t been the same since.

Does this mean that every romance in which sex is frankly talked about or depicted is a ripoff of one of these two authors? Are the heroines and heroes these authors created the only genuine archetypes of modern romance, and everything else we’ve read is a copy? No. But they’re responsible for a sharp turn in how characters were portrayed. The previous definitions of what a hero and heroine could be and had to be were thrown out. Years later, with the advent of erotic romances and paranormal romances, we’ve again seen a sharp turn. Good girls no longer take their definition of good from their social world, but from their own feelings and convictions. We’re seeing a range of behavior in romances today that has never been seen before, and I’m not just talking about sex. Who created the first paranormal heroine in the black tank top and leather pants, that gal who carries a knife/sword/Uzi/nasty big honking weapon? I don’t remember who, but this kind of heroine is an archetype all her own now. She saves the world herself, with or without help from a stalwart hero, because she’s the only one who can. It’s a far cry from the demure girl next door stories of decades ago. And yet…we have the Amish and evangelical romances, in which heroes and heroines never behave in a less-than-chaste manner, and women are very conventionally womanly in their pursuits, and so on.

In fact, today romances are all over the map. Nobody has to participate in the hive mind to produce an acceptable romance, but we all do, because we’re all exposed to the same mass media, the same world events, etc. There need be no precise copying of specific authors’ heroes or heroines, no swiping of exact storylines, because at any given moment many writers are writing similar stories. There is no one single story that is the only romance, and any innovation that is popular will provoke a host of imitators. These are repeated elements, not wholesale lifts from another author’s work. The occasional writer may attempt to copy the winning style of a successful author. But it’s only the writer bereft of talent who plagiarizes, who steals from another author word for word.

Which returns us to the question of what is genuine, original art. The largest amount of appropriating in art is by the original artist. Painters do cycles of paintings all on the same topic, exploring changes in various elements. Romance authors write book after book using the same basic heroine and hero character types they have developed from current archetypes. If they discover they have created an interesting minor character in one story, they’ll take a version of that character to explore in another story. Georgette Heyer’s These Old Shades was a virtual rewrite of her own earlier novel, The Black Moth. Names were changed, and the direction of the plot changed, but her every-inch-the-aristocrat duke was the same man, redeemed.

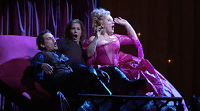

Would it surprise you to know that the photos I’ve sprinkled through this are from an opera, Le Comte Ory, whose composer, Gioachino Rossini, took major parts of it from a previous opera he’d created? It shouldn’t. Artists borrow from themselves all the time. It’s when they appropriate from others without permission that there’s a problem.