Qualified to Read Romance?

Recently a Romance Writers of America chapter decided not to accept Gay, Lesbian, Bi, or Transgender (GLBT, or LGBT) romance manuscripts in its annual writing contest. In previous years, this chapter had done so, and various LGBT manuscripts had won. There was no shortage of judges for such a contest, so no claims of not having any background to judge such mss. were made. It all seemed to come down to what felt unfamiliar and unwelcome to some people in the chapter. To say this sparked vast numbers of outraged responses (see Smart Bitches for a sample) is to understate the situation. I’m not going to pillory that chapter here, but the incident has caused other RWA chapters to review their own contest rules.

Whenever a group cries foul, all of us who judge, edit, or write romances pause and think seriously about what our standards are, and what they’re based on. Over the years I’ve edited several romance manuscripts with lesbian lead characters and with African American characters. I’ve been aware that, not being either L or AA, I can’t fully share the authors’ perspective because I don’t have the direct experience. Thus it is possible I might be applying white hetero standards to their stories that I shouldn’t. But then again, a good romance is a good romance, no matter whom it’s about.

Sometimes my lack of specific knowledge has skewed my opinion of the details of a story, though. If I don’t know what terms are considered romantic versus what are considered vulgar within a certain group, then I can’t tell an author if she has crossed the line. All I can do is apply the more general standards common in published romances. I’ve tripped up in the past over regionalisms, too, so it’s not merely a sexual preference or racial issue. For instance, years ago I thought “cranking” a car was a strangely old-fashioned term, but then I learned it was a current southern usage. Similarly, until serious athletic gear became standard American clothing, spandex was only in girdles, and thus a mention of it was unsexy, I thought. Times change. On the other hand, regardless of my lack of personal experience with being Italian American, or coming from Texas, or being part of a huge clan of cousins, uncles, aunts, and grandparents, I feel confident that I can fairly judge, either as an editor or a reader, what constitutes an appealing and effective romantic take on those elements. As a reader, I know it in my gut, without consulting any issues of familiarity. After all, it’s impossible for me to have firsthand experience of the Tudor court of Henry VIII, but I can recognize a well-written take on that historical era and its major actors. So can you.

What is romantic to me today is not what I thought exciting ten years ago, but a well-told story should always be identifiable to a conscientious judge, editor, or reader. Many times, I have evaluated a well-written manuscript and had to tell the author that the story and the way it was told were not in fashion and her chances of being published were slim. Today, with self-publishing or assisted epublishing available from many sources (including Arrow, check out About Us), those novels, perhaps antique in style or content, or too outre for mass publishers to take a chance on, but still wonderful stories, now can be read by the public.

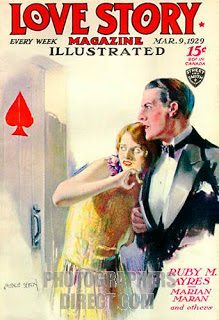

This controversy has reminded me how little most of us know before we start a new experience. People often joke that it’s a shame no one has to take a maturity test in order to get a marriage license or have a baby. The fact is, we embark on new experiences throughout our lives for which we have zero background. Luckily, there is no qualification to read a romance other than an interest in doing so.